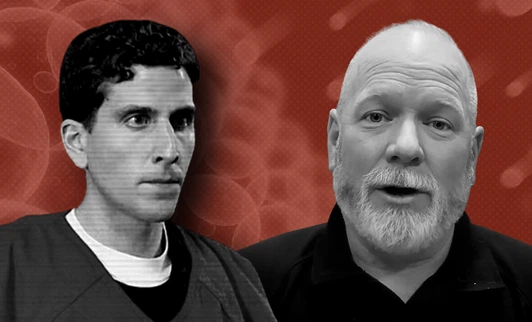

Did the police violate the guy accused of killing four college students in Idaho Fourth Amendment rights?

Much has been made of the fact that police in this instance relied on genetic genealogy and DNA evidence to issue the arrest warrants.

Nonetheless, the use of such technology, and how it was most likely utilized in this instance, was legal, as was the use of cell site location information (CSLI) to monitor the suspect’s phone’s travels.

A partly redacted affidavit issued by police provides a fuller picture of the circumstances of the case and the evidence justifying the suspected killer’s arrest.

At the Crime Scene, DNA

The four murder victims, the all University of Idaho students, were discovered in a residence near the Moscow campus. On November 13, 2022, between 4:00 and 4:25 a.m., each was stabbed to death.

In a second-floor bedroom, a guy and a female victim were discovered stabbed to death.

Two female victims were discovered on the third floor in a single bed. A tan leather knife sheath was found next to one of the murdered females.

DNA from an unknown guy was discovered on the sheath’s button snap during a forensic investigation.

Proof of Cell Site Localization

On August 21, some months before the killings, a county sheriff in Moscow stopped the suspect for a traffic infringement.

He was driving a white 2015 Hyundai Elantra with Pennsylvania license plates at the time. He gave the officer his mobile phone number.

When a mobile phone is switched on, it receives and transmits a signal to a nearby cell tower.

When the phone travels, the signal easily flows from one tower to the next in the same direction.

Cell phone service companies maintain track of every mobile phone that uses their services, including all cell site location data (CSLI).

This data offers a “map” of where the phone traveled when turned on.

Police enforcement requested and received a search warrant for historical phone records pertaining to the suspected murderer’s phone number.

According to the data, the account was formed on June 23, 2022, for a subscriber with the suspect’s name and an address in Albrightsville, Pennsylvania.

A check of the historical CSLI data indicated that the phone had pinged cell towers in the region of the murder site 12 distinct times previous to the day of the murders—always in the nighttime or early morning hours.

In fact, three months before the killings, from 10:34 p.m. to 11:35 p.m. on August 21st, the suspect’s phone pinged a mobile tower that offered service to the King Road house for nearly an hour.

At 2:42 a.m. on the night of the killings, CSLI shows the phone at or near the suspect’s apartment in Pullman, Washington.

During the following five minutes, it proceeds south towards Pullman before ceasing to ping, suggesting that the phone was switched off or placed in aeroplane mode.

The phone signal recovered two hours later, at 4:48 a.m., pinging towers along state route 95 south of Moscow and Blaine, Idaho.

The phone then traveled south to Genesee, Idaho, west to Uniontown, Idaho, then north before returning to the suspect’s residence around 5:30 a.m.

The CSLI footprint of the alleged murderer’s phone matches the hours, dates, and routes of the white Elantra observed in video security footage retrieved from his neighborhood, university, and the roads and highways between his apartment and the King Road property.

Does acquiring the murder suspect’s CSLI information violate his Fourth Amendment rights? Absolutely not.

The United States Supreme Court upped the threshold for granting police access to SCLI in Carpenter v. United States (2018). Before, the government would seek a court order under the Stored Communications Act to get mobile phone records (SCA).

Since the information was in the hands of a third party, the requests did not have to satisfy the “probable cause” threshold required to obtain a search warrant. As a result, the mobile phone user might have no reasonable expectation of privacy over his CSLI.

Carpenter changed that practice by requiring police to get a search warrant for each CSLI that involves more than seven days of data. The cops in Idaho were completely cooperative. They initially requested a search warrant for two days of CSLI data concentrated on the slayings.

They then sought and secured a warrant for all CSLI from June to December after evaluating that information.

The data offers a devastating picture of the suspect’s phone’s locations in the months preceding up to the killings, as well as on the night of the crimes. Authorities will say that the suspected murderer scoped out the murder spot a dozen times before the quadruple deaths in the dead of night.

They will very definitely claim that based on the phone’s travel map on the night of the killings, the suspect left his house around 2 a.m., drove to Idaho, shut off the phone while committing the murders, and then turned it back on once the crimes were completed.

When superimposed over the movement of the white Elantra, the mobile phone’s movement seems pretty convincing.

Molecular Genealogy

What about the DNA evidence’s admissibility? On December 27, police in Pennsylvania recovered garbage from the suspect’s family home in Albrightsville.

The Fourth Amendment does not bar the warrantless search and seizure of rubbish outside of a residence, according to the Supreme Court’s ruling in California v. Greenwood (1988).

The DNA detected on the part of the salvaged garbage was matched to the DNA acquired from the crime scene material. The lab stated that at least 99.9998% of the male population could be “ruled out as a possibility of being the suspect’s biological father.” Simply put, the garbage DNA came from the father of the person who left the DNA on the sheath at the crime site.

The affidavit is intentionally obscure about how the police arrived at this conclusion, but it’s not difficult to figure out what transpired. Police, without a doubt, sent the sheath DNA to two distinct tests: one to forensically identify the DNA profile for admission into court, and the other to develop a SNIP-based genetic profile that would allow them to link that person’s DNA to a close family.

SNIP is an abbreviation for single-nucleotide polymorphism, which is a sequence variant that helps geneticists to identify close relatives via genetic genealogy.

Authorities were able to connect the suspect’s and his father’s profiles, and since the suspect is an only child, this was sufficient to establish probable cause and arrest him for the killings.

- Kamala Harris Congratulates Donald Trump on Presidential Election Win

- Raiders Fire Luke Getsy: Offensive Coordinator Axed After 2-7 Start

- James Van Der Beek diagnosed with cancer, at 47: ‘I’m Feeling Good’

- Quincy Jones Dies at 91: Music Legend & 28-Time Grammy Winner

- 20 Spooky Halloween Nail Designs You Must Try

If the case proceeds to trial, the government’s case will be based not just on the CSLI, DNA, and genetic genealogy evidence stated above, but also on witness testimony, audio evidence, video footage of the defendant’s white Elantra’s travels, and other evidence of the defendant’s internet activity.

The Moscow murder suspect, like all defendants, is deemed innocent unless and until proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. Nonetheless, there is no question that the CSLI or DNA evidence in this instance does not violate the Fourth Amendment.